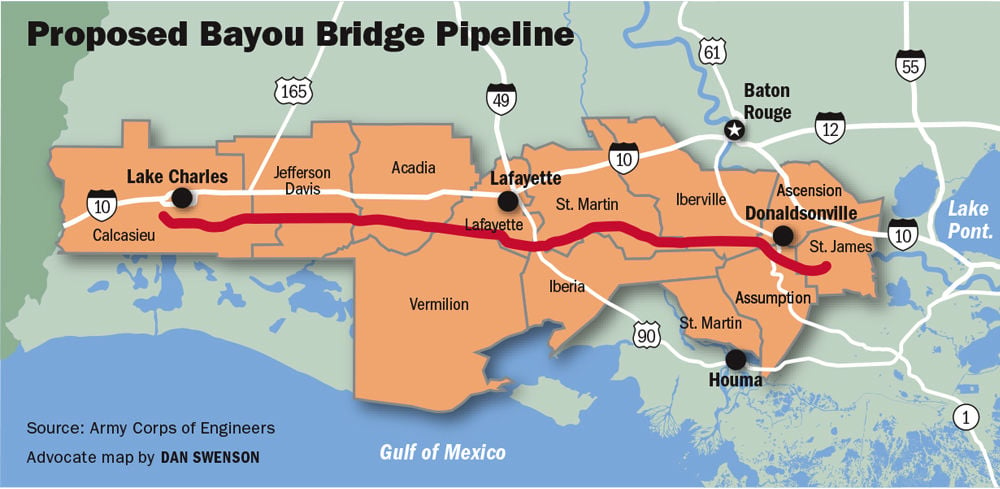

Environmental groups in Louisiana are gearing up to fight a proposed 162-mile oil pipeline that would cut through the Atchafalaya Basin, a project involving the same companies building the controversial Dakota Access pipeline between North Dakota and Illinois.

The proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline would cross 11 parishes, beginning in Calcasieu and ending in St. James. It would link Louisiana refineries to a major hub in Texas that connects to larger pipelines throughout North America, including the Dakota Access.

The new pipeline would cross a south Louisiana landscape that's already a dense patchwork of smaller oil and gas pipelines, but some environmental groups say it's time for the state to take a close look before adding another.

"We've let so much be destroyed, and it's just time to stop it," said Anne Rolfes, director of the New Orleans-based Louisiana Bucket Brigade.

The Bucket Brigade, the Louisiana chapter of the Sierra Club, the Gulf Restoration Network, the Atchafalaya Basinkeeper and five other environmental and conservation groups have joined in a formal request that the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers deny the federal permit needed for the pipeline.

A public hearing on the permit application is set for 6 p.m. on Jan. 12 in Baton Rouge.

Past pipeline projects in the state have been approved with little fanfare, but Rolfes and others hope media coverage of protests in North Dakota over completing the Dakota Access pipeline could bring more scrutiny to the Louisiana project.

"There is no doubt that current events are making people more passionate," Rolfes said.

She said Louisiana, long known as an oil-and-gas state, should be shifting away from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

"Putting in another pipeline does not help that transition," Rolfes said. "… We are already getting nailed by floods and other calamities that are caused by the warming of our atmosphere."

The Bayou Bridge Pipeline project is being jointly pursued by subsidiaries of Phillips 66, Sunoco Logistics and Energy Transfer Partners.

All three companies have a stake in the Dakota Access Pipeline. The latter two recently announced a merger and are major players in pipeline operations across the U.S.

The companies argue the $750 million project will be a boon for Louisiana's economy and actually improve the safety of oil transport in the state.

"Currently, most of the crude oil being delivered to refineries along the Gulf Coast is coming in by truck, rail and marine, all of which are more dangerous to the environment than underground pipelines," Alexis Daniel, a spokeswoman for the project, said in an email.

Environmental groups opposing Bayou Bridge take issue with that, saying building a pipeline doesn't necessarily mean rail, boat and truck transport will stop.

The groups also worry that state and federal regulators don't have the resources to ensure pipelines are maintained properly.

"There are numerous leaks from pipelines that are affecting water quality in Gulf and in the watersheds. These pipelines are put in and then they get old and they are not maintained and they leak," said Haywood Martin, chairman of the Sierra Club's Delta Chapter in Louisiana.

Environmental groups also have raised concerns about impact of building a new pipeline through historic wetlands in the Atchafalaya Basin.

Several pipelines already crisscross the vast swamp, and Daniels said 88 percent of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline will be built next to existing oil and gas infrastructure, which should mitigate the environmental impact.

That's little comfort to Dean Wilson, executive director of the conservation group Atchafalaya Basinkeeper.

Wilson said the Basin ecosystem has already been fouled by dirt dug out to install prior pipelines and then left piled high along the trench, serving as a levee to block the natural flow of water through the swamp.

"Instead of covering them up, they leave the spoil banks," Wilson said. "They go for miles through the swamp."

In written objections to the Bayou Bridge permit, the environmental groups argue that no clear process has been laid out to ensure wetlands would be returned to their natural state, with no spoil banks left behind.

The Louisiana Crawfish Producers Association-West, a group of Basin crawfishermen who have long complained about pipeline spoil banks, has joined the environmental groups in opposing the proposed pipeline.

A public hearing on the proposed pipeline is set for 6 p.m. on Jan. 12 in the Oliver Pollock Room of the Galvez Building at 602 N. Fifth St. in Baton Rouge.

The hearing is being jointly held by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which decides whether to issue the permit, and the state Department of Environmental Quality, which must give its OK on water quality impacts as part of the Corps' permit approval process.