BAYOU SORREL -- Down Louisiana 3066 and the Lower Grand River, past the middle of swampy nowhere, rests a cypress marsh hamlet of oyster shell roads, elevated houses, above-ground swimming pools and all manner of flat-bottom boats. This is where the geography maze that is the Atchafalaya Basin unfolds in a breathtaking flat canvas of forest, wetlands and pockets of semi-navigable water.

To the novice -- and even some old-timers -- it's impossible to tell where one bayou begins and another ends. Mound Bayou, Salt Mine Bayou and Cannon Bayou all nestle around Sorrel, a name given to a bayou and the river that runs through it, as well as to this unincorporated village of fewer than 250 people.

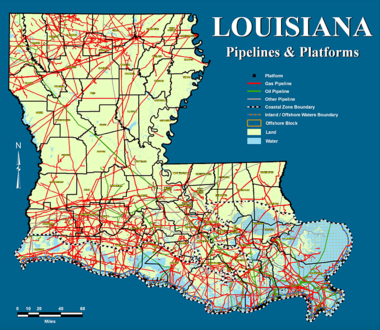

There's another maze here, too. It's one of pipeline canals etched in every crisscrossing direction through the basin by oil and gas companies that directly employ more than 64,000 people in Louisiana. They carry the state's most lucrative natural resources from the ground to refineries and petrochemical plants across the coast.

Since oil was discovered in Louisiana in 1902, there's been a steady tension between those who make their livelihood fishing, trapping and hunting the creatures living in the basin, and those who make money by extricating the crude oil and gas created millions of years ago from the fossilized remains of marine organisms that once lived here. The problem, in a nutshell, is there's no feasible way to get this fuel out of the ground and transported to a location where it can be refined or processed without some damage to the natural landscape.

And that, complain fishers and environmentalist activists, is altering drainage and water flow, eroding the land and increasing flood risks. It's one of several reasons that south Louisiana is disappearing into the Gulf of Mexico.

"We need to get out of the fossil fuel business," said Anne Rolfes, founding director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, a New Orleans-based environmental health and justice organization. "We need to stop building pipelines. It's causing catastrophic problems to our environment."

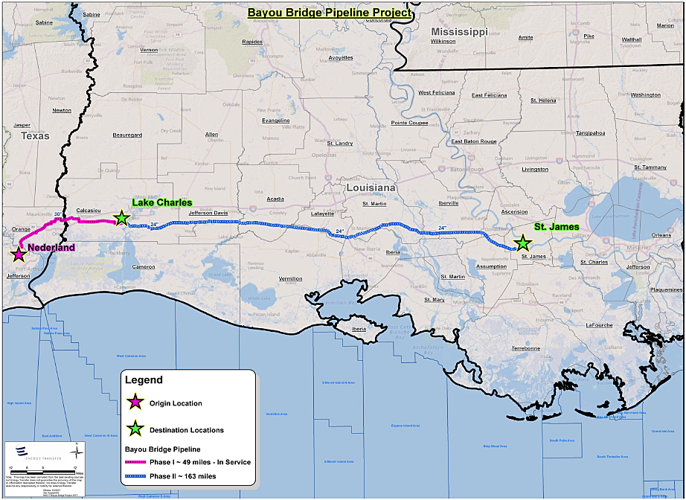

Against this backdrop comes a company that wants to build the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, a $670 million project that would run 162 miles through the Atchafalaya Basin and across 11 parishes, beginning in Calcasieu and ending at an oil terminal in St. James. Supporters say the pipeline, which would link a major oil-and-gas hub in Texas with refineries in Louisiana and along the Gulf Coast, would be far superior to trains, trucks and barges for moving oil.

"It's the safest and most economical way to transport crude," said Gifford Briggs, vice president of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association. "People should be celebrating this project."

Competing economic interests

Those who live in Bayou Sorrel do so for pretty much one reason: to carve out a living off the land. This is where common folk, as well as larger-than-life reality television personalities Willie and Junior Edwards of "Swamp People", work backbreaking days year-round hunting alligator and catching fish, crab and crawfish to pay the bills. Some still hunt the Atchafalaya for pelts, but not so much since the fur industry fell into decline around the turn of the 21st century.

"This is how people here have lived for centuries," said Dean Wilson, a resident and executive director of Atchafalaya Basinkeeper, a nonprofit formed to protect and restore the largest wetland (931 square miles) in the United States.

Many of these people worry the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, despite numerous safety and environmental repair assurances from company officials, will further damage their hunting and fishing grounds. They fear for their economic future.

What's undeniable is that this state, and its government, are economically powered by the oil and gas industry. According to a 2014 report by LSU economist Loren Scott, the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil and Gas Association and Grow Louisiana Coalition, the industry was responsible for 64,669 direct jobs (287,000 including related work), $20.5 billion in household earnings and almost $74 billion in sales to Louisiana companies in 2011.

"It is the engine that makes the difference," Scott said. "The energy industry, and its accompanying multiplier effects, has been a powerful engine for economic growth in Louisiana." Without the taxes generated by the petrochemical industry, he said, state government "would be out of business."

Bayou Bridge backers, in promotional material, estimate that the pipeline will create 2,500 construction jobs, $17.6 million in sales taxes during construction and $1.8 million in property taxes during the first year it is in service. Due to the nature of how a pipeline operates, as well as technology improvements, the number of permanent jobs directly linked to the project is just 12.

Critics, on the other hand, including more than 100 who showed up at a Jan. 12 permit hearing in Baton Rouge, argue:

- There are already too many basin-damaging pipelines in the Atchafalaya

Scott Eustis, a wetlands specialist with the Gulf Restoration Network, told protestors at a Baton Rouge rally that the Bayou Bridge Pipeline "is the biggest, baddest thing I've seen in my career."

"There is no pipeline in Louisiana that is safe," geographer Ezra Boyd of DisasterMap.net said during a Jan. 10 conference call discussing a report he co-authored with the Louisiana Bucket Brigade to show that the state recorded 144 pipeline accidents in 2016.

That point was driven home Thursday night (Feb. 10) when fire erupted as six workers were cleaning a 20-inch Phillips 66 gas line at Paradis. Two workers were burned, and one was missing. Sixty homes were evacuated, and parts of two highways were closed.

The Bucket Brigade also released a report showing Energy Transfer Partners, the company behind the proposed Bayou Bridge Pipeline, had reported accidents across the country in 2015 and 2016, including 35 pipeline incidents.

One of the industry's lobbyists at the Jan. 12 hearing, former U.S. Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-La., acknowledged the global warming argument, saying the push to shift the world away from fossil fuel energy is laudable. "But that day is not today," she said, adding that pipelines are the safest and best option for transporting crude oil through the state.

State officials have not raised any objections to the project. Indeed, state Reps. Nancy Landry, R-Lafayette, and Stephen Dwight, R-Lake Charles, have both written letters supporting the proposal.

Two government permits are needed for the pipeline, from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for the overall project and from the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources because the pipeline would traverse part of the state's coastal zone in two parishes, Assumption and St. James. Officials say there is no timetable for deciding whether to issue them.

The Bucket Brigade, along with the Louisiana chapter of the Sierra Club, the Gulf Restoration Network, the Atchafalaya Basinkeeper and other environmental and conservation groups, have asked the Corps of Engineers to deny the federal permit.

A rare political fight

That there is protest at all is a bit surprising. Typically a pipeline project, even one as large as this, would garner little public attention in Louisiana and sail through the regulatory and permitting processes.

But the Louisiana protestors were emboldened in 2015 when President Barack Obama rejected the proposed 1,179-mile Keystone XL pipeline that would carry oil from Canada to the Gulf Coast. More encouragement came in 2016 when protesters and a Native American tribe persuaded the Corps of Engineers to consider an alternate route for the 1,172-mile Dakota Access Pipeline, a $3.9 billion project to move oil from North Dakota to an oil hub in Texas.

"This victories have given us hope," Rolfes said. "Often (hearings) are held merely to satisfy critics before projects are given the rubber stamp. This time will be different. This time our voices will be heard."

The victories might have been short-lived, however. On Jan. 24, President Donald Trump, in his first week in office, reversed Obama's decision on Keystone and signed a document clearing the way for government approval of the Dakota Access pipeline.

The company building the Dakota Access Pipeline, Energy Transfer Partners, is also involved with the Bayou Bridge project, according to permit applications on file with the state. It's in a joint venture with subsidiaries of Phillips 66 and Sunoco Logistics.

In fact, the two projects are linked: The Dakota pipeline would carry crude from North Dakota's Bakken Formation to a site near Nederland, Texas, then a recently completed pipeline built by the same group will transport it to Lake Charles to connect with the Bayou Bridge Pipeline for delivery to refineries and ports across south Louisiana.

Currently, much of that oil is moved by rail and barge, initially to Port Manchac in south Tangipahoa Parish then across Lake Ponchartrain to a Phillips 66 refinery at Alliance, on the West Bank in Plaquemines Parish.

"The pipeline is merely a delivery system, similar to FedEx, to help fill an already existing need," said Alexis Daniel of Granado Communications Group, a Dallas public relations firm representing Energy Transfer Partners.

The 24-inch diameter pipeline would cross eight Louisiana watersheds, according to materials filed with the permit application. In the Atchafalaya Basin, 77 acres of wetlands will be permanently altered and 171 acres of wetlands temporarily affected by construction.

That concerns Jody Meche, a commercial crawfisherman from Henderson. He said he's not necessarily opposed to the pipeline but worries it will aggravate water flow issues caused by existing pipelines.

"My business has been hurt over the past decade," he said. "I don't want it to get any worse."

Restoring the damage

A fact sheet, published in January by those backing the project, states: "Bayou Bridge is committed to restoring 100% of any affected area -- at the company's own expense -- if there are any impacts from construction or during long-term operations."

Such promises ring hollow for Rolfes, of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade. "The evidence is clear these companies say whatever they need to in order to get a permit and then refuse to take responsibility for the damage they cause after the fact," she said. "How much more has to be destroyed before we say it's time to stop?"

Russel Honore, a retired U.S. Army general from Louisiana and leader of the Green Army coalition of environmental groups, argues the underlying problem is that Louisiana lacks the regulations or the enforcement capabilities to hold oil and gas companies responsible for inspecting and maintaining pipelines. "And don't expect the state Legislature, which is too friendly with industry, to do anything to force these companies to address past problems," he said.

The Bayou Bridge Pipeline, said Wilson of Atchafalaya Basinkeeper, would run alongside an existing pipeline, widening a right of way that he said is already out of compliance with permits. He said he's not necessarily opposed to the project or oil and gas exploration, but he does want the Corps of Engineers to ensure all existing right of ways in the basin are in compliance and that all existing pipelines operated by those behind the Bayou Bridge project are reviewed for compliance before permits are approved.

"We'll see what happens," he said. "At the moment the corps doesn't have a single person in the basin enforcing these permits."

Basin crawfishers and environmentalist activists have complained for decades about work done by oil and gas companies. Despite bans on the practice, they say, dirt is left to pile up on canal banks, which interferes with the natural water flow and destroys crawfish habitat.

Bayou Bridge representatives, in meetings with local groups, have said the pipeline's sponsors plan "to restore all project areas to pre-construction contours and elevations and to restore work areas in the Atchafalaya Basin back to the natural grade as compared to the adjacent undisturbed land or wetlands." Their permit application makes the same pledge to "minimize impacts on the environment."

Eustis, of the Gulf Restoration Network, said the concern goes behind the environment. He worries that areas in the basin hit hard by the Louisiana Flood of 2016 in August might not be able to recover due to the pipeline's potential to interfere with stormwater draining into existing bodies of water.

There's no dispute that significant damage has been done to the Atchafalaya Basin over the past century, not only by the oil and gas industry but also by the mass cutting of cypress trees and the clearing of wetlands for agriculture. The effect has been significant not only in the basin downstream, because the erosion of marshes has led to the loss of coastal lands to the Gulf of Mexico.

Louisiana has a $50 billion, 50-year plan to fight the loss of coastal land. But it doesn't have all the money, and some of the projects in the plan are unproven.

Gov. John Bel Edwards is pushing to sue oil, gas and pipeline companies to pay for the historical damage that he and others allege the industry has done to the coast. Briggs, of the Louisiana Oil and Gas Association, however, says lawsuits aren't necessary, and that the state should do its job of enforcing its own coastal-use permit requirements.

"The way pipelines are built today is far safer and involves much more technology and testing than in the past," Briggs said. "Is anything 100 percent certain? No, but the pipeline will be built and operated in the safest way possible."

If it does come to pass, everybody in the Atchafalaya Basin hopes he's right.

"I've seen the damage caused by doing it wrong," said Rusty Comeaux, a Lafayette native who works in the oil fields and regularly hunts and fishes the Atchafalaya. "The state, or whoever, needs to stay on top of these people and make sure everything they're supposed to do actually gets done."

. . . . . . .

CORRECTION: An earlier version of this story gave an incorrect size for the diameter of the Bayou Bridge Pipeline, based on a corporate document.